Huge Potential for Japanese Offshore Wind, But Challenges Remain

On the last day of June, the auction closed for the second round of offshore wind projects, totalling 1.8GW in capacity. Japan’s huge offshore potential — forecast at exponentially more than the nation’s entire energy needs — continues to attract attention both at home and abroad. However, challenges remain around supply chains, logistics and the regulatory environment; issues that need to be resolved if offshore is to significantly contribute to Japan’s decarbonisation shift.

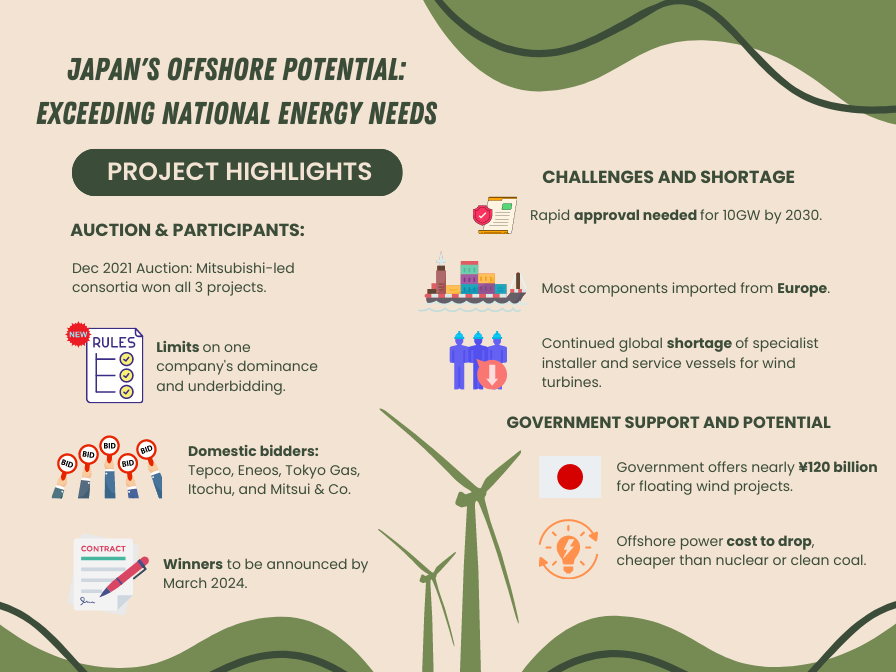

Following the results of the December 2021 auction, in which consortia led by trading house Mitsubishi Corp. landed all three projects, new rules were implemented for the latest round. These include restrictions on one company sweeping the board on bids and excessive underbidding on the price electricity will be delivered at.

Although the new guidelines also forbid firms from announcing their participation in the auction, the Nikkei has reported that Tepco, Eneos, Tokyo Gas and trading houses Itochu and Mitsui & Co. are among the domestic bidders on the four projects. Winners are due to be announced between the end of this year and March 2024.

Going, going, gone

Japan’s first major commercial offshore project, run by the Akita Offshore Wind Corp. (AOW) and led by Marubeni, came online in stages between the end of 2022 and early this year off the coast of Akita prefecture. The 140MW capacity more than doubles the total generative power in the Japanese offshore sector, but the fact that this was the culmination of a seven-year process sheds light on the kinds of timelines involved.

The projects from the first and second auction rounds will also take years to start providing electricity, with the first slated to come online in late 2028. A rapid acceleration of the approval and deployment processes will be necessary if the government’s target of 10GW of offshore power by 2030 is to be hit.

AOW installed 33 turbines built by Denmark’s Vestas and each reaching the approximate height of a 40-storey building, utilising the specialist vessel Seajacks Zaratan, illustrating the complexity of the supply chain and logistics involved in such large-scale projects. The majority of the components, including monopiles and turbine blades, had to be imported, mostly from Europe. Meanwhile, UK-based Seajacks (owner of the Seajack Zaratan and world leader in such vessels) was acquired in 2021 by Monaco-headquartered Eneti from a Japanese consortium that included Marubeni.

There is already a worldwide shortage of the specialist installer and service vessels required for wind turbines which is expected to continue as the number of new projects rises, according to shipbroker Clarksons. Similar to the timeframes for offshore projects, shipbuilding is a multi-year endeavour and so the shortfall cannot be made up in a hurry.

In addition to the ship shortage, investment in Japanese ports and regulatory reforms are needed to increase the number of facilities able to handle the specialist vessels and their huge cargoes.

Help is on its way

The Japanese government is offering support for offshore technology, detailed in the ‘Introduction of Japan’s Offshore Wind Policy’ paper from the Ministry of Economy Trade and Industry in March. Announced were subsidies of up 119.5 billion yen ($850 million) in total through the Green Innovation Fund for development and demonstration projects for floating wind turbines.

All of the currently approved and tendered projects are fixed-bottom turbines in relatively shallow water, but the vast majority of Japan’s potential capacity lies in deeper water, requiring the newer tech of floating turbines. The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that Japan’s total potential offshore wind generation is nine times its projected energy demand for 2050, with the vast majority of that to come from deep-water wind farms. Plants further from the shore are also less likely to provoke opposition from local residents, though objections from fisheries groups will still be a potential issue.

Hands and winds across the sea

Also in March, the Japan Wind Power Association (JWPA) and Norwegian Offshore Wind, representing more than 900 companies between them, signed an agreement to collaborate on offshore wind technology development and supply chain, citing the importance of being early movers in the nascent market.

The IEA predicts that the experience and knowhow gained in executing projects in Japan, along with bolstered domestic supply chains, will rapidly decrease the cost of offshore power, and by 2030 it will be cheaper than new nuclear or so-called clean coal plants.

Despite the challenges, the combination of immense potential, government backing, burgeoning knowhow and the imperative of a shift in energy systems should ensure Japan’s offshore sector enjoys a boom for many years to come.

By: Gavin Blair

To find out more about hot roles in sustainability area and elsewhere please contact us at +81-3-5962-5888 or email us at info@slate.co.jp

Current openings:

• Technical Project Managers

• Technical Project Engineers

• Service Managers

• Project Developers

• Commercial Managers